History of an Art Form

The greatest joy I have in studying history is coming across those amazing “nexus” moments, those moments where you realize “holy crap, if X didn’t figure this out, and Y didn’t make that choice, then not only would Z have turned out differently but A, B, and C might not even exist”. It’s those “EUREKA!” moments that makes this little hobby of mine worth while.

Lately I’ve been trying to flesh out my understanding of the history of music. Not Bach, Brahms, and Beethoven, but Chuck Berry, Jimmy Yancey, and Muddy Waters. Not only am I a big fan of rock & blues, but I find the whole history of it to be utterly fascinating. As an art form, well, there are definitely richer, more textural forms of music out there, but as an evolving cultural movement, it’s inspired, and fascinating, and controversial, and revolutionary, and damn sexy.

This is American classical music, not born out of an age of royalty and patronage, but cooked in the cauldron of Jim Crowe oppression, Depression-era poverty, Dust Bowl hardship, and Edison electricity. It comes from the fertile loins of the uniquely American amalgam of races and cultures. There is no other place on Earth where this unique confluence of happenstance existed, and there is no other place on Earth where the music we now know as Rock & Roll could have possibly been invented.

This is American classical music, not born out of an age of royalty and patronage, but cooked in the cauldron of Jim Crowe oppression, Depression-era poverty, Dust Bowl hardship, and Edison electricity. It comes from the fertile loins of the uniquely American amalgam of races and cultures. There is no other place on Earth where this unique confluence of happenstance existed, and there is no other place on Earth where the music we now know as Rock & Roll could have possibly been invented.

As much as I love it, I’m also terribly ashamed my knowledge of it is not incredibly deep. I’ve only just recently listened to Dylan’s “Blonde on Blonde” end-to-end! I’ve really missed out on an awful lot of classic recordings, and therefore am clearly missing out on a lot of great stuff and a lot of great context. It’s embarrassing, really. So, in order to correct this gross oversight, I decided to go back and not only acquire, but really listen to, all the classic recordings throughout rock history.

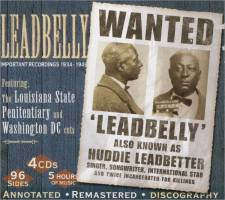

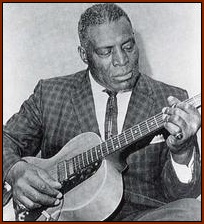

The other day I was perusing my favorite used music store (http://www.turnitup.com/) and came across the 4 CD box set Leadbelly: Important Recordings 1934-1949. Leadbelly (aka Huddie Leadbetter) is one of the preeminent, influential figures, having been inducted to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as an Early Influence in 1988. He’s definitely known as a forefather of the Blues, but only when I gave this box set a solid listen did I appreciate just how much of an influence he truly was, and just how reflective of an entire chunk of neglected history his music truly is.

Let’s just start with the recordings themselves. These are gritty. Full of scratches and stutters and variations. No dreaded autotuning here.This man is the real deal, with all his pockmarks, rough edges and foibles there for all to see. In today’s overproduced age, where anyone can be a star thanks to audio waveform manipulation, this realism is incredibly refreshing.

————————————————————————————————————

Modern-day marvels:

————————————————————————————————————

Assuming you lived through that, try this:

————————————————————————————————————

Important Recordings causes a time machine effect as well. A trip through this collection is a trip back to Precambrian rock, soul, and R&B. I love finding older versions of modern songs. It’s like finding a dinosaur skeleton and realizing it’s the great-grandpappy of the blue jay. On this box set, you’ll hear 60+ year-old versions of such great songs like “C. C. Rider” (later covered by John Lee Hooker, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley & the Grateful Dead); “The Gallis Pole” (retitled “Gallows Pole” & recorded by Led Zeppelin); “Midnight Special” (famously covered by Credence Clearwater Revival); “Rock Island Line” (a Johnny Cash staple and a famous John Lennon bootleg); “How Long” (covered by Eric Clapton on his excellent From the Cradle CD); an amazingly uptempto “In New Orleans” (aka “House of the Rising Sun”, inarguably the biggest hit of the Animals); and “Where Did You Sleep Last Night”, which was eventually covered by, of all people, Nirvana on their outstanding Unplugged album. Hearing these songs in their near-original state is akin to going to the Smithsonian to see the Model T or the first light bulb.

As great as these old finds are, the real heart and soul of Important Recordings is reflected in the other tracks, the tracks that haven’t made it into the vernacular of modern music. These are tracks like the repentent “I’m Sorry Mama”, the work-weary “Boll Weevil”, the sorrowful “Po’ Howard”, the fairly creepy “Black Snake Moan”, and the lamenting “My Friend Blind Lemon”. These are songs from the forgotten era of the sharecropper, a hardscrabble life of poverty where your only support is from faith, friends & family. You’ll also hear more than a handful of Negro work songs like “Pick a Bale of Cotton”, and chain gang songs like “Take This Hammer”, complete with the percussive “huh” grunting by unnamed background vocalists. Give these a good listen, try to put yourself in the shoes of these men in their time, and tell me it doesn’t give you the chills.

I love the place, absolutely love it, loved it from the beginning. I was there during the opening, 8-hour concert on Labor Day weekend in 1995, where I saw everyone from Chuck Berry to Johnny Cash to Dr. John to Aretha Franklin to Iggy Pop. That was a fantastic experience. The next day I saw James Brown sauntering through the crowd, surrounded by some of the biggest, scariest bodyguards imaginable, on his way into the Rock Hall. I’ve been back several times since, and love it more and more every time I go. For me, it goes beyond being a fan of rock music. My love of rock & roll dovetails nicely into my love of American history.

I love the place, absolutely love it, loved it from the beginning. I was there during the opening, 8-hour concert on Labor Day weekend in 1995, where I saw everyone from Chuck Berry to Johnny Cash to Dr. John to Aretha Franklin to Iggy Pop. That was a fantastic experience. The next day I saw James Brown sauntering through the crowd, surrounded by some of the biggest, scariest bodyguards imaginable, on his way into the Rock Hall. I’ve been back several times since, and love it more and more every time I go. For me, it goes beyond being a fan of rock music. My love of rock & roll dovetails nicely into my love of American history. Rock & roll is uniquely American because of it’s “origin story”. Rock’s primary grandfather was The Blues. Political correctness aside, The Blues was the black man’s music. It’s basically a lament about hard times and suffering set to a quick-paced but rough tempo. The Blues was fostered in a segregated South and derives directly from music sung by plantation slaves. This is Part I of why Rock is uniquely American, it’s the only positive thing to ever come out of our slaveholding past. Without the caustic cauldron of atrocity known as antebellum slavery, and the emotional agony of Jim Crow, the genetic material of The Blues would not have been created. No Blues, no Rock.

Rock & roll is uniquely American because of it’s “origin story”. Rock’s primary grandfather was The Blues. Political correctness aside, The Blues was the black man’s music. It’s basically a lament about hard times and suffering set to a quick-paced but rough tempo. The Blues was fostered in a segregated South and derives directly from music sung by plantation slaves. This is Part I of why Rock is uniquely American, it’s the only positive thing to ever come out of our slaveholding past. Without the caustic cauldron of atrocity known as antebellum slavery, and the emotional agony of Jim Crow, the genetic material of The Blues would not have been created. No Blues, no Rock. Then there’s Jazz. Jazz, in my view, represents the independent American mentality applied to music. People wanted to play what they wanted to play, and wanted to hear what they wanted to hear. It’s improv, blending, mixing things up, and doing what you want. It’s throwing away musical convention, just like we threw away monarchial convention. We tossed out the King and made our own government, then we tossed out musical conformity and made our own Jazz. It’s the Declaration of Indepence set to music.

Then there’s Jazz. Jazz, in my view, represents the independent American mentality applied to music. People wanted to play what they wanted to play, and wanted to hear what they wanted to hear. It’s improv, blending, mixing things up, and doing what you want. It’s throwing away musical convention, just like we threw away monarchial convention. We tossed out the King and made our own government, then we tossed out musical conformity and made our own Jazz. It’s the Declaration of Indepence set to music. Rock has then been changed and modified and altered by so much more since then: the injustice of the Vietnam War draft, the poverty of inner cities, the rebellion of angsty white suburbanite teens, plus America’s penchant to abuse mind-altering substances …. All of these things are, again, uniquely attributable to the U.S. and the unique mix (or train wreck, if you prefer) of our culture.

Rock has then been changed and modified and altered by so much more since then: the injustice of the Vietnam War draft, the poverty of inner cities, the rebellion of angsty white suburbanite teens, plus America’s penchant to abuse mind-altering substances …. All of these things are, again, uniquely attributable to the U.S. and the unique mix (or train wreck, if you prefer) of our culture.