Mammoth Cave National Park, Kentucky

I was a freshman in high school when I was introduced to Dungeons & Dragons. I was smack in the middle of the target demographic for Gary Gygax’s brainstorm. I read a lot of Greek myth as a boy (I was more fascinated by Odysseus and Bellerophon than I was by dinosaurs). Rankin-Bass’ 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘏𝘰𝘣𝘣𝘪𝘵 introduced me to Tolkien’s 𝘓𝘰𝘳𝘥 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘙𝘪𝘯𝘨𝘴, which I read voraciously and repeatedly. The 𝘚𝘪𝘯𝘣𝘢𝘥 movies came out in the prior decade and hit rerun television so often I almost knew them by heart. Then, of course, there was 𝘔𝘰𝘯𝘵𝘺 𝘗𝘺𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘯 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘏𝘰𝘭𝘺 𝘎𝘳𝘢𝘪𝘭 (Ni!). Between a deep understanding of these pop-culture references, my coke-bottle glasses, and a total lack of athleticism, it was inevitable I’d play D&D. It was the perfect fit: a social activity that required imagination, a propensity for dick jokes, and math. Lots of math.

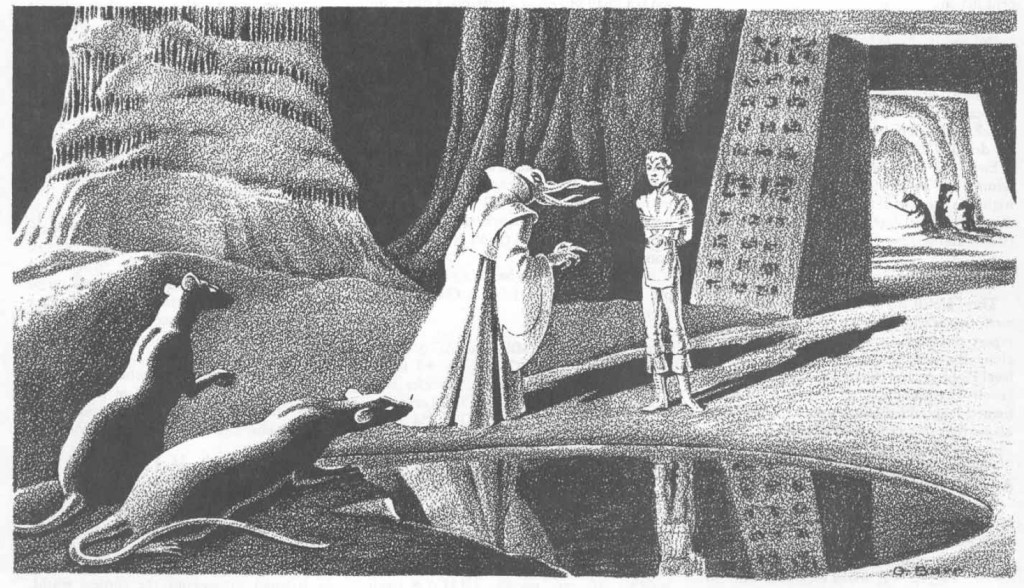

One of D&D’s milieus is the underground. “Dungeons” is in the name, after all. Not just creepy basements under spooky castles, but vast networks of deep tunnels; expansive caverns housing fantastic cities; underground rivers filling huge underground lakes; all filled with horrific monsters and evil civilizations. One of my favorite adventures was Descent Into the Depths of the Earth. You play a band of heroes (of course), hot on the trail of evil underground-dwelling elves called “drow”. Traversing miles of tunnels, wide enough for trade caravans, you search for clues in warrens of troglodytes, and negotiate with schools of walking, cannibalistic fish-men called “kuo-toa”. Danger lurks around every dark corner. Adventurers succeed or die gruesome, horrible deaths. Great fun.

Of course, it’s all fantasy. All these fictional worlds, whether Dungeons & Dragons, or Riftworld, or Middle Earth, or Pandora, or whatever, are fantastic places that can’t possibly exist. Physics, gravity, geology, hydrology: they simply don’t work that way. You can’t have flat planets, you can’t have floating islands, you can’t fly a dragon to the moon, and you can’t have huge underground cities connected by caravan-wide tunnels.

Or can you?

Websites around the world proclaim this or that to be the “world’s biggest” or “world’s best”, but you rarely believe such exaggerations. There’s always disappointment, always overselling, always that feeling of being let down, just around the corner. But when I went to the original natural entrance of Mammoth Cave, a gaping maw at least 30’ wide, I knew this was, indeed, something special.

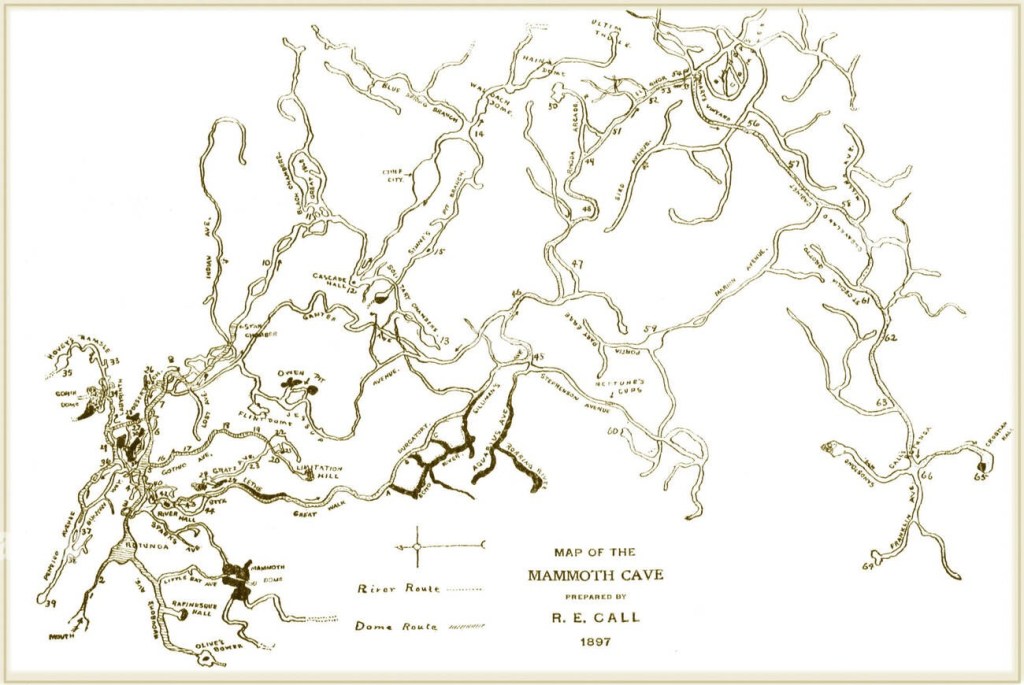

The cave system contains over 400 miles of passages, with more being discovered every year. Some of these passageways are 30’ wide, and tall enough for a school bus. Many of them are easy walking (constructed walkways mostly for accessibility and protecting fragile formations). Deeper down are the windy, spelunk-worthy crawl-ways, but there’s also an underground river where they used to offer boat tours! It’s hard to explain how large and fantastic these caves are without seeing them, and unfortunately I didn’t have a digital camera all those years ago when I toured. I’ll throw links at the bottom of this post, you can see for yourself the scale of the thing.

I love letting my imagination run wild when I go to these places. How can you not envision pre-Columbian Lakota buffalo hunting when you visit Big Sky Country? How can you not imagine great whaling ships when you visit New Bedford, or the struggles of Martin Luther King when you walk the streets of Birmingham, or immense alien spaceships while standing in the shadow of Devil’s Tower? Or drow and kuo-toa whilst inside Mammoth Cave?

I still play D&D from time to time. It hits differently than it used to, of course, but it’s still fun to get together with a bunch of like-minded nerds to roll dice and tell dick jokes and swing vorpal swords at green dragons. It’s cheaper than playing poker, beats sitting around a bar ruining your liver, and there’s nothing but crap on all these streaming services anyway. If you can’t be in the woods, on a mountain overlook, or deep in a cave system, grab some dice and roll up a gnome illusionist.

================

Links: