World War 0.1

I hate ignorance. I especially hate it in myself.

It’s one thing to not have all the facts, or to misinterpret the ones you have, or to not grasp the subtlety of a particularly complex situation. But to miss something important in its entirety, that’s ignorance. And to miss something important in your own chosen endeavor, that’s just negligence!

I went to Fort Necessity completely unaware of it’s significance. It was just a spot on a National Park Service map. I thought it had something to do with the Revolution or something. I was so undeniably, completely wrong, so utterly ignorant, it’s shameful. Fort Necessity, as it turns out, is probably the singular site in all the NPS that has truly global significance. This is a site that marks a minor event in American history, but a huge event in world history.

The events unfolded in this manner:

In the time before the American Revolution, England and France vied for the continent. England, of course, had the 13 original colonies along the Atlantic Ocean. France had her own territory, in the north along the Saint Lawrence Seaway and lakes Erie and Ontario, and a spot of land at the foot of the great Mississippi River known as Louisiana. England wanted to move into the interior, and France wanted to use the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to connect Quebec and New Orleans. For years, the two great powers, with centuries of enmity between them, would dance around each other in the New World.

In 1753, the governor of Virginia heard the French built forts on the south shores of the two big lakes, on land England thought was hers. The governor sent a small squad, led by a young lieutenant, George Washington, to warn the French of their trespass. Washington found himself rudely rebuffed by the French.

In 1754, newly promoted Lt. Col. Washington led a small regiment to help defend a small English fort near the Ohio River, only to find the French had taken over and built their own. Washington’s regiment made camp, and the young colonel thought to engage local Seneca chief Half-King and convince the French to depart. It was meant to be a parlay, backed by a subtle threat of superior numbers and a home-field advantage.

In 1754, newly promoted Lt. Col. Washington led a small regiment to help defend a small English fort near the Ohio River, only to find the French had taken over and built their own. Washington’s regiment made camp, and the young colonel thought to engage local Seneca chief Half-King and convince the French to depart. It was meant to be a parlay, backed by a subtle threat of superior numbers and a home-field advantage.

To this day, it is unsure who fired the first shot. It is often debated, but in reality, it doesn’t matter. What matters is a shot was fired. A skirmish erupted, and the young colonel was victorious. Thirteen Frenchmen lay dead, 21 were captured and led back to Williamsburg.

Here is where the tales diverge. In America, we are told that Washington, realizing a counterattack was imminent, led his regiment back into the wild and built a small palisade called Fort Necessity. Unable to solidify alliances with the local Seneca and other Indian tribes, Washington’s 300+ men fought and were defeated by 700 French and Indian troops. Washington had no choice but to surrender and take his men back to Virginia. It would be Washington’s only surrender of his entire career. The French and Indian War, as Americans would come to know it, would be fought, and the French would be pushed out of North America.

In Europe, however, a totally different story is told. There, that ill-fated shot would be used as propaganda by both France and England to ratchet up tensions between the two European powers. The resultant battle between relatively small forces in North America would ignite a massive conflict on the European continent known as the Seven Years War. It was truly the first actual World War, involving many countries across Europe. On the one side, England and her allies (Prussia, Portugal, and some German states) would fight Austria, Sweden, Saxony and France. Russia, in typical fashion, would switch sides in the middle of the thing. Even the Dutch were involved when one of their own colonies was attacked in modern-day India.

This is the tale that Americans aren’t told. Hell, we’re barely taught anything about the French & Indian War! But the Seven Years War cost almost one and a half million lives. It redrew the map, not only in Europe and North America but even in Africa, the Carribbean, and the Indian subcontinent. It severely weakened France, factored in their decision to assist America in their battle for independence, and set the stage for the French Revolution. It ended the Holy Roman Empire entirely, and rose Great Britain to the role of the dominant maritime and colonial power in the world. They would rule large tracts of land from the southern tip of Africa through the Middle East to India, Australia, and Canada for two hundred years until a later World War would undo the effects of this first one or, as I call it, World War 0.1.

This is the tale that Americans aren’t told. Hell, we’re barely taught anything about the French & Indian War! But the Seven Years War cost almost one and a half million lives. It redrew the map, not only in Europe and North America but even in Africa, the Carribbean, and the Indian subcontinent. It severely weakened France, factored in their decision to assist America in their battle for independence, and set the stage for the French Revolution. It ended the Holy Roman Empire entirely, and rose Great Britain to the role of the dominant maritime and colonial power in the world. They would rule large tracts of land from the southern tip of Africa through the Middle East to India, Australia, and Canada for two hundred years until a later World War would undo the effects of this first one or, as I call it, World War 0.1.

Fort Necessity taught me a lot about this period of world history, more than high school or college taught me. Americans aren’t taught this at all, except those who study third-year world history. It’s forgotten, lost, or simply uninteresting. I wonder if it’s ignorance or arrogance. Our own involvement in the Seven Years War was small, and when it did happen, we weren’t really America at that point, so in our eyes, it didn’t even matter. But there are events that happen outside of our cloistered continent that are important, even without us. We need to pay heed, observe and learn of those things outside of our borders (both borders of space and of time).

We are not the center of the universe. We are not even the center of the world. We cannot afford to pay attention to only those things that revolve around us.

[Pics on this post are mine and thusly copyrighted. More are here.]

===============================================

Links:

Fort Necessity National Battlefield

Seven Years War on Military History Online <– such an interesting site I added it to the blogroll

The only problem I have with proclaiming Lincoln as the “greatest American” is his actions really only saved the country. When I hear “greatest American”, I think globally: which American did the most for the world? Now that is an entirely different question. Sure, some could extrapolate “well, America is the greatest country, and Lincoln saved America, so Lincoln is the greatest”. That not only shows a grotesque level of hubris, it’s not really accurate. America wasn’t a world player for nearly a century after Lincoln’s time. We were an isolationist nation. We were protected on two fronts by mighty oceans, and only had two neighbors. No threats = no conflict = no interest in the world. Plus we were a nation of immigrants, collectively giving Europe the big middle finger as we went on our way, making our own prosperity (and driving the native population into their graves, but that’s the subject for yet another post). Saying Lincoln was a great world figure is simply disingenuous.

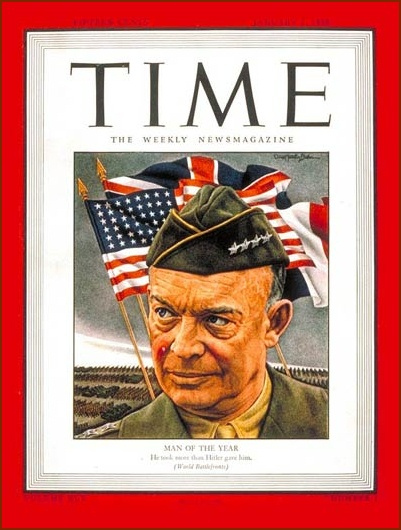

The only problem I have with proclaiming Lincoln as the “greatest American” is his actions really only saved the country. When I hear “greatest American”, I think globally: which American did the most for the world? Now that is an entirely different question. Sure, some could extrapolate “well, America is the greatest country, and Lincoln saved America, so Lincoln is the greatest”. That not only shows a grotesque level of hubris, it’s not really accurate. America wasn’t a world player for nearly a century after Lincoln’s time. We were an isolationist nation. We were protected on two fronts by mighty oceans, and only had two neighbors. No threats = no conflict = no interest in the world. Plus we were a nation of immigrants, collectively giving Europe the big middle finger as we went on our way, making our own prosperity (and driving the native population into their graves, but that’s the subject for yet another post). Saying Lincoln was a great world figure is simply disingenuous. This leads me to my own approach to the “Greatest American” question. First, did the individual have a postive, global impact; and second, did the individual act with the best of our core American principles (life, liberty, pursuit of happiness, etc.)? I say Ike deserves serious consideration as the Greatest American under that context, and I say it for one big reason: World War II.

This leads me to my own approach to the “Greatest American” question. First, did the individual have a postive, global impact; and second, did the individual act with the best of our core American principles (life, liberty, pursuit of happiness, etc.)? I say Ike deserves serious consideration as the Greatest American under that context, and I say it for one big reason: World War II.