Community College English 101

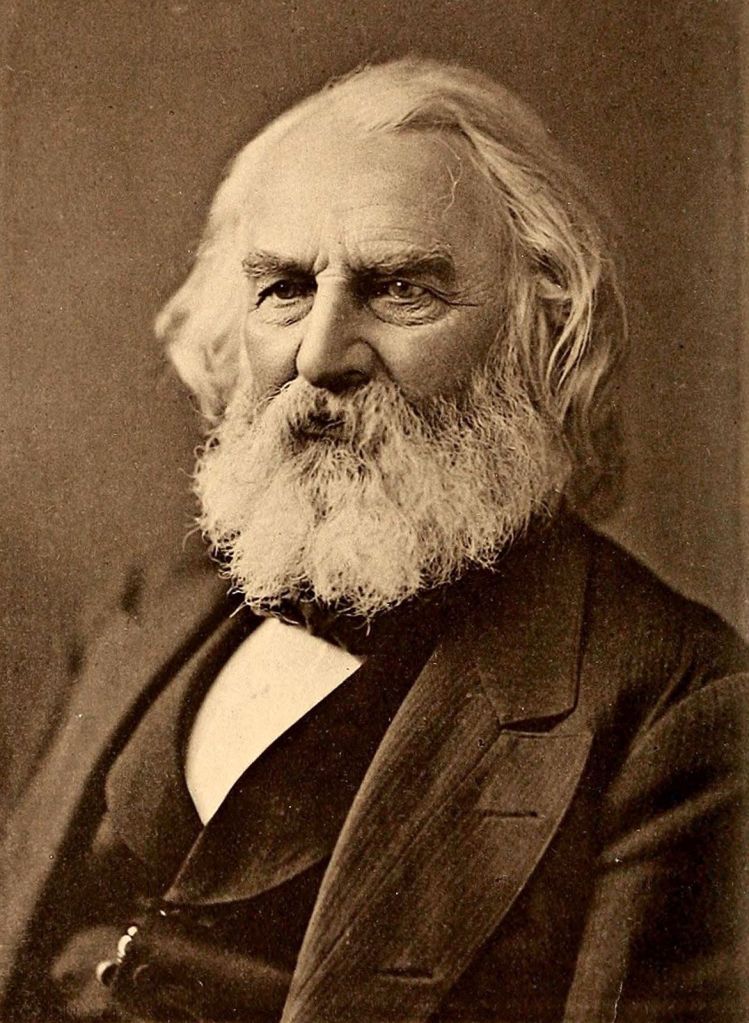

The Longfellow House in Cambridge is a beautiful, historic house. Built in 1759 in the Georgian style, it was originally occupied by Jamaican plantation owner John Vassall. A staunch loyalist, Vassall saw the writing on the wall and fled to England, just in time for George Washington to use it as headquarters during the early years of the Revolution. After the war, the house was purchased by Washington’s apothecary general, Andrew Craigie. His financial acumen was less than stellar, forcing his widow Elizabeth to take in boarders in 1819, including the soon-to-be-renowned poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Later, Longfellow received the home as a wedding gift, and it stayed in the family or their trust until the entire building, its furnishings, and the grounds were donated to the National Park Service.

That’s all nice, but when I hear “Longfellow House”, I am reminded of my goofy college days.

My family was never particularly well-off. I was a sharp student, but we didn’t have the means to send me to college. So I took what I earned from part-time jobs and went to community college.

Springfield Tech was a good school with a solid electronics program. I already knew Ohm’s Law, Coulomb’s Law, and a variety of formulas and principles, so I had a bit of a head start. I loved those classes, the labs, mathematics, even physics (although it was taught by a professor I’m certain died three years prior).

Then came the dreaded mandatories. First day of first semester, when I had barely any understanding of what to expect, began English 101. I have long forgotten the name of the professor, but I’ll never forget his entrance. Tweed jacket and vest. Dignified salt & pepper beard. And a beret. Yes, a goddamned beret.

I don’t remember all of Professor Beret’s lessons, the one that sticks in my mind is our foray into Robert Frost. I’m talking about that old standby, which most kids learn in high school, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. The discussion came down to the old, self-wankery standby: “what does this poem mean to you?”

Me, being a bit overeager to discuss such heady topics in the presence of adults, instead of with a class full of hormonal teenagers, piped up with “well, a guy is evaluating his life choices. Shall he return to the life he knows, in comfort, or should he take another path, to see if he can become something special.”

“Um, no,” said Prof. Beret. “It’s about suicide.”

What? Well, apparently, if you decide to take that lesser-traveled path, you want to die by freezing to death …

Holy leaping Christ, what the fuck?

Anyway, that lesson tarnished me on poetry forever. I realized that not only do I not easily pick up on symbolism, but people who put poetry up on philosophical pedestals are fucking crazy.

In preparation for this essay, I read many poems from Longfellow: The Complete Poetical Works. Most of his works are direct homages to nature and the art of living. There’s not a lot of deep symbolism, just well-structured odes, definitely tame by today’s standards. There’s no doubt he was big for his time, but now it’s all quaint recollections of seeing a shooting star and such.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorites:

The Burial of the Minnisink

On sunny slope and beechen swell,

The shadowed light of evening fell;

And, where the maple’s leaf was brown,

With soft and silent lapse came down,

The glory, that the wood receives,

At sunset, in its golden leaves.Far upward in the mellow light

Rose the blue hills. One cloud of white,

Around a far uplifted cone,

In the warm blush of evening shone;

An image of the silver lakes,

By which the Indian’s soul awakes.But soon a funeral hymn was heard

Where the soft breath of evening stirred

The tall, gray forest; and a band

Of stern in heart, and strong in hand,

Came winding down beside the wave,

To lay the red chief in his grave.They sang, that by his native bowers

He stood, in the last moon of flowers,

And thirty snows had not yet shed

Their glory on the warrior’s head;

But, as the summer fruit decays,

So died he in those naked days.A dark cloak of the roebuck’s skin

Covered the warrior, and within

Its heavy folds the weapons, made

For the hard toils of war, were laid;

The cuirass, woven of plaited reeds,

And the broad belt of shells and beads.Before, a dark-haired virgin train

Chanted the death dirge of the slain;

Behind, the long procession came

Of hoary men and chiefs of fame,

With heavy hearts, and eyes of grief,

Leading the war-horse of their chief.Stripped of his proud and martial dress,

Uncurbed, unreined, and riderless,

With darting eye, and nostril spread,

And heavy and impatient tread,

He came; and oft that eye so proud

Asked for his rider in the crowd.They buried the dark chief; they freed

Beside the grave his battle steed;

And swift an arrow cleaved its way

To his stern heart! One piercing neigh

Arose, and, on the dead man’s plain,

The rider grasps his steed again.

=======================

Despite my difficulties with a certain English 101 professor, I did get a great education at that school.

Links:

Longfellow House National Historic Site

George Washington’s Revolutionary War Itinerary