Freedom and Repatriation

The Lincoln Memorial might be our greatest national symbol. It’s everywhere: our currency, our iconography, our culture. Presidents have spoken in front of it. Martin Luther King gave one of his most moving speeches from its stairs. Numerous musical artists including, famously, opera singer Marian Anderson, performed to massive crowds gathered there. It’s appeared in everything from Mr Smith Goes to Washington to Forrest Gump to Planet of the Apes. There’s not much I can add to the lore of it, other than to say every American should make the pilgrimage at least once.

Instead of posting some weak trivia list about the Lincoln Memorial, I’m going to write about The 1619 Project.

————————

The 1619 Project was a collection of essays published by the New York Times in 2019, and again in book form in 2021. I’ll let historian and journalist Lerone Bennett, Jr. explain:

A year before the arrival of the celebrated Mayflower, 113 years before the birth of George Washington, 244 years before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, [a] ship sailed into the harbor at Jamestown, Virginia, and dropped anchor into the muddy waters of history. It was clear to the men who received this “Dutch man of War” that she was no ordinary vessel. What seems unusual today is that no one sensed how extraordinary she really was. For few ships, before or since, have unloaded a more momentous cargo.

Bennett, Lerone Jr, Before the Mayflower, 1962

That ship was the White Lion, the year was 1619, and its cargo was “twenty and odd” captives from west Africa.

The central premise of The 1619 Project is this: the collective history Americans hold dear grossly underrepresents the impact and long-lasting effect of slavery on this country. In a series of long-form essays, a variety of authors, journalists, and historians lay out the case that slavery affected America’s viewpoint on everything from property rights to citizenship to economics to the very definition of democracy. These essays are hard-hitting, blunt, and brutal, and together assemble a very sobering read. Of course, they cover the obvious, like the 3/5th clause of Constitution and the collaboration between the KKK and law enforcement in the Jim Crowe South. But they also make links that might not be so obvious, including throwing some shade on our best president, Abraham Lincoln.

Before I go on, let me state up front that this is not intended to demean or degrade the Great Emancipator. Frederick Douglas called him “Tender of heart, strong of nerve, of boundless patience and broadest sympathies, with no motive apart from his country. […] Take him for all, in all Abraham Lincoln was one of the noblest, wisest and best men I ever knew.” Booker T Washington said “[M]ay I say, you do well to keep the name of Abraham Lincoln permanently linked with the highest interests of the Negro race. He was the hand, the brain, and the conscience that gave us the first opportunity to make the attempt to be men instead of property.“ But W.E.B. Dubois was probably more accurate in his own assessment: “Abraham Lincoln was perhaps the greatest figure of the 19th century. Certainly of the five masters – Napoleon, Bismarck, Victoria, Browning and Lincoln, Lincoln is to me the most human and lovable. And I love him not because he was perfect but because he was not and yet triumphed.”

Lincoln, as great as he may have been, had one small problem, a bit of a character flaw, or at least a lapse in judgement. That problem was the American Colonization Society. Founded in 1816, the ACS was an unlikely group of early abolitionists, Southern slaveholders, and politicians of all persuasions. These men felt the chief concern of the time had a solution, and that solution was the repatriation of freed Blacks to Africa.

The abolitionists were afraid freed Blacks would simply never fit in, becoming a permanent underclass throughout the North. Slaveowners felt these freedmen would work tirelessly to free their brethren, perhaps engaging in violence or insurrection or even murder. Politicians were afraid they would taint voter rolls, influence elections, and threaten established power. Honestly, it’s hard to say their fears were unjustified, and Lincoln himself seemed to share those fears. Although he was not a member of the ACS, Lincoln espoused the idea of Black relocation as early as 1851. By 1862, he created the position of Commissioner of Emigration, and convinced Congress to appropriate $600,000 to ship freed Blacks to another country.

Black freedmen were appalled. They wanted to be free, yes, but not like that. By this time, some 240 years had passed since the White Lion docked. Generations of their forebears lived in houses, worked the soil, raised their children, all on these shores. They knew not of other lands, knew not of Africa, nor of any other land but America. Repatriation was a deplorable option. The United States, as flawed as it was, as dangerous and hostile as it was to slaves and freedmen alike, was still their home.

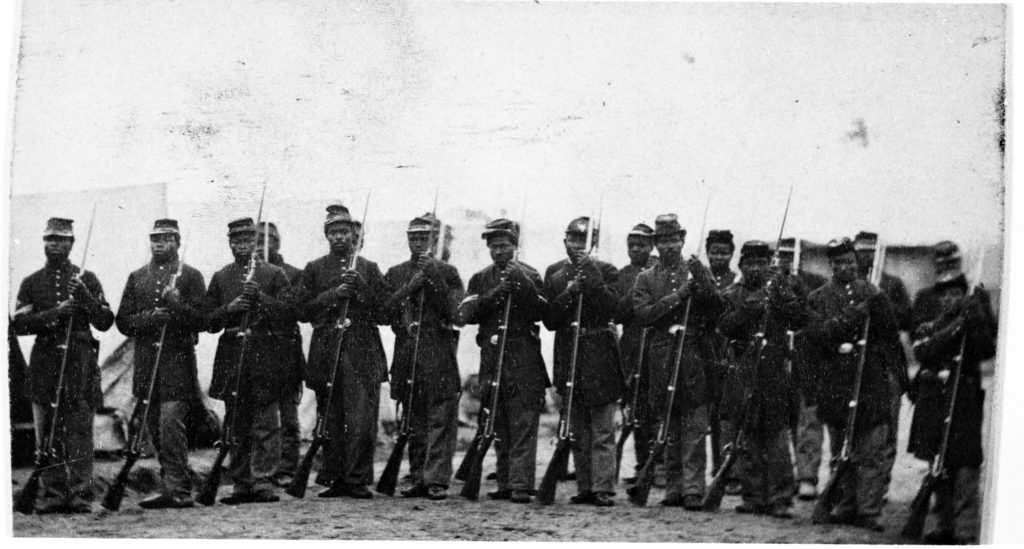

They would prove this in short time. After Lincoln’s official Emancipation Proclamation — which did not include any references to repatriation — some 200,000 Black men served in the Union army. That’s an astounding 78% of military-aged men! They took the Civil War personally, it was their fight, for their freedom, in their country.

———

Lincoln was an imperfect man. His emigration plan was a terrible idea. But he listened to the criticisms, dropped it, and changed the course of American history. Unfortunately, we still stumble across repatriation now and again. In this country, we debate the disposition of the Dreamers, young people smuggled into this country when they were very small, at no fault of their own, who are often threatened with deportation to countries they’ve never known. And right now, in the Middle East, ancient animosities are used as excuses to forcibly evict people off lands they’ve inhabited for decades if not centuries. In these cases, and many, many others, nobody cares. These “intolerables” would be better off gone, some would think.

But no one should be forced from the only home they’ve ever known. This has to be a fundamental precept of freedom.

———

I highly recommend The 1619 Project. I consider it vital reading for anyone wishing to understand this country, past and present.

———

Links: